Game Production & Direction Tips

stuff that I learned

So I learned some things over the years

I want to share some tips with things that I learned over the years. They worked for me, and may be helpful to you or inspire you to find a way that works for you. Game development is hard, and there very few certainties, but if we pool our experiences we may find some common truths, or things that helps us move forward.

So here goes. 20 tips that came to mind recently. There may be more, I will make another post if that is the case.

1. Keeping your project on track with timeboxing

A game project that runs on schedule has constraints in place that force decisions.

Estimations will always be imperfect, even with context and experience, making it nearly impossible to consistently predict when development will reach certain milestones.

Timeboxing is a powerful tool if projects need to stay on schedule.

This technique involves setting a specific objective to achieve within a certain timeframe, which focuses the team, forces decisions and induces creativity.

It effectively transforms the ‘project-manager’ role (focus on planning and reporting) into a ‘producer’ role: working with the team to surface problems and generate solutions that fit the time allowed.

The timeboxes can be broken down from a high-level development schedule into smaller steps required to achieve for example the ‘pre-production’ phase.

The key elements of a good timebox are:

•A well-defined objective, usually in the form of a problem definition (and not a solution) and a quality-bar.

•An appropriate amount of time that respects the overall project-plan

•Accept that the outcome of a timebox is the reality of the product that will be taken forward (do not allow ‘debt’ to be carried forward)

2. Find a balance between adding new things and smart reuse

When starting a project, play to your strengths.

New, fresh experiences are hiding in uncertainty, but too much uncertainty makes a project unwieldy and adds risk.

To balance this, leverage what already exists. By building on what exists, you can focus on expanding and enhancing what you have. This approach brings both freshness and a manageable level of uncertainty..

So, when starting, think about what you have:

•💽 What reusable code (or code concepts) exists?

•🖼️ What art or animations can be reused or be retrofitted?

•🧩 What design concepts are transferable?

•✍️ What has the team learned that you can leverage?

It may sound ‘cheap’ to reuse but think about how you can ‘plus’ existing content, or how a new context transforms it.

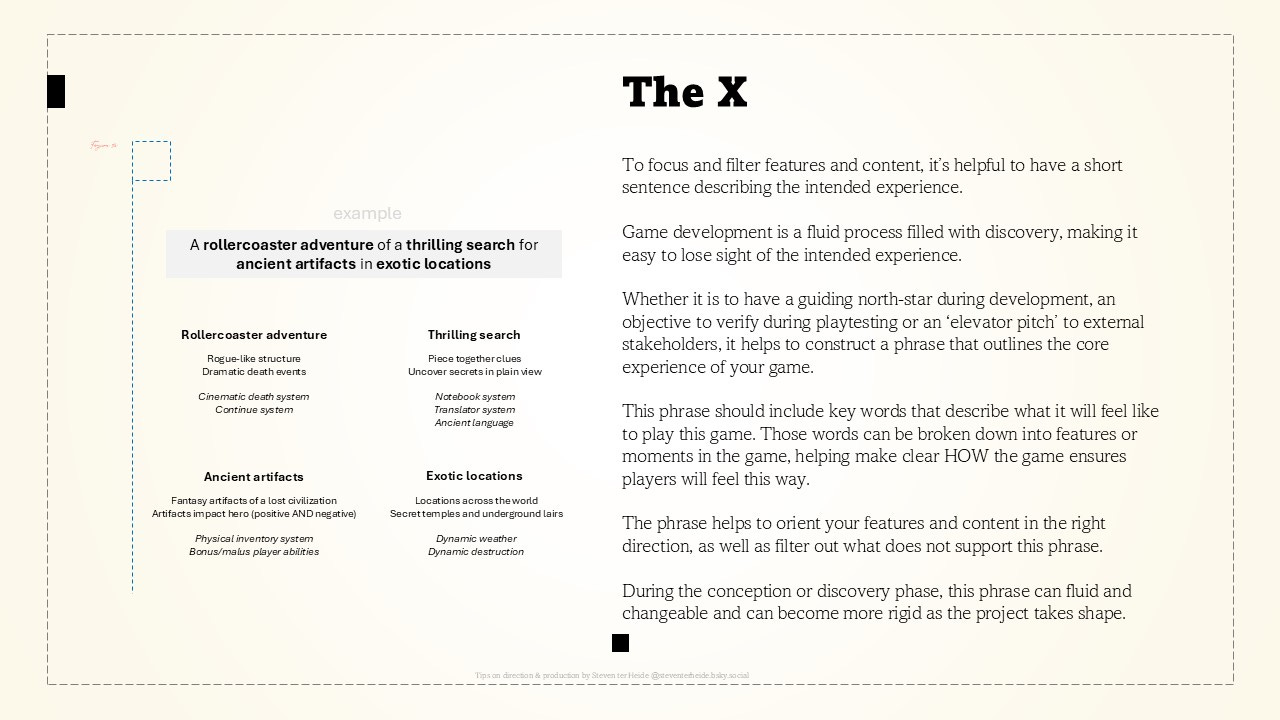

3. How to set an actionable direction for your game

To focus and filter features and content, it’s helpful to have a short sentence describing the intended experience.

Game development is a fluid process filled with discovery, making it easy to lose sight of the intended experience.

Whether it is to have a guiding north-star during development, an objective to verify during playtesting or an ‘elevator pitch’ to external stakeholders, it helps to construct a phrase that outlines the core experience of your game.

This phrase should include key words that describe what it will feel like to play this game. Those words can be broken down into features or moments in the game, helping make clear HOW the game ensures players will feel this way.

The phrase helps to orient your features and content in the right direction, as well as filter out what does not support this phrase.

During the conception or discovery phase, this phrase can fluid and changeable and can become more rigid as the project takes shape.

4. Fun is something that needs to be worked at

Fun is subjective and the result of many factors. But with the focus on what can be controlled, we can trust the process to get us results.

We should do the things we have control over:

•👓 Research; learning all you can about a feature, from comparative games, other media, life itself.

•🧰 Prototype; Make it playable, in whatever form. But remember that polish can make or break the prototype.

However, recognizing fun can be challenging early in development and can be lost later on.

We have to trust our instincts and subjective judgement:

•👃 Intuition; What feels like it would be fun?

•⚖️ Evaluate; Be brutally honest, walk away from the feature if needed, or push for polish if that is what it requires.

5. Your planning should adapt to what you know about your game

The best plan is made in response to the game.

Planning a game is difficult due to uncertainties, ambiguities and subjectivity.

A playable (portion of) game will help to align the understanding (of the team) of what the game will be. The game may even ‘tell you’ what it is, where a certain feature demonstrates its ability (or inability) to carry the game.

To build a good plan, focus on:

•🕹️ Early playable(s); Aim to have a playable version as soon as possible, even if it’s incomplete or just a single feature.

•🤸 Team play-session; Organize a session where everyone plays the game.

•📊 Honest evaluation; Assess what works well, what needs improvement, and what’s missing to create a coherent final product.

Remember: the objective is to align the team on what the game currently is and what it needs.

6. A way to add focus and have a shared objective in teams

Having focused milestones will help show clear progress (a valuable motivator), force decisions and integrates all elements of the game.

Milestones can be hard to define, with different disciplines working on different timelines.

Adopting a 'trailer' approach can provide the necessary focus for milestones. Trailers can be created at any stage even with work-in-progress content, as long as the intentions are clearly represented.

The ‘trailer’ approach is particularly useful because:

•🔎 Focuses on the key game elements, decisions have to made and priorities set

•🤼 All disciplines need to pitch in and integrate (facing problems early)

•🥉 Elements need to have sufficient quality, receive early polish and bug- fixing that help de-risk and set quality standards

Bonus: It creates a record of key moments throughout development

7. Idea generation can be guided, and it starts with a good problem definition

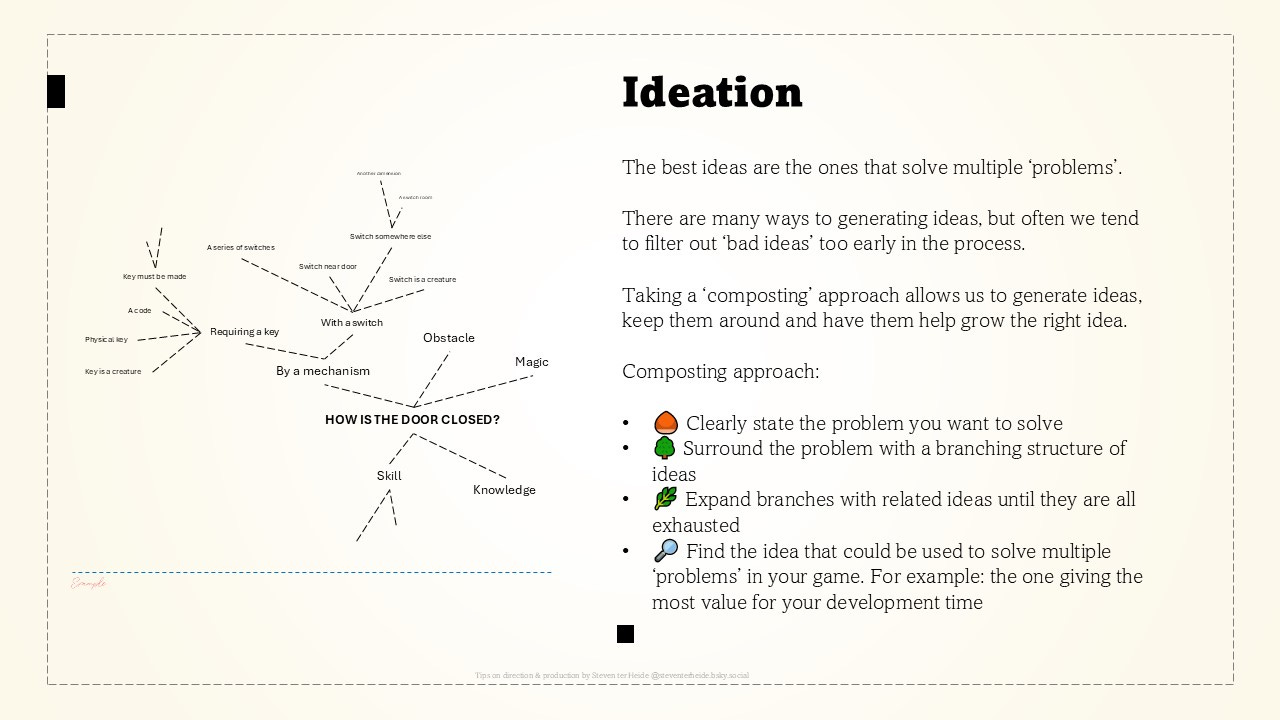

The best ideas are the ones that solve multiple ‘problems’.

There are many ways to generating ideas, but often we tend to filter out ‘bad ideas’ too early in the process.

Taking a ‘composting’ approach allows us to generate ideas, keep them around and have them help grow the right idea.

Composting approach:

•🌰 Clearly state the problem you want to solve

•🌳 Surround the problem with a branching structure of ideas

•🌿 Expand branches with related ideas until they are all exhausted

•🔎 Find the idea that could be used to solve multiple ‘problems’ in your game. For example: the one giving the most value for your development time

8. The right amount of design documentation can help to focus the idea or avoid pitfalls

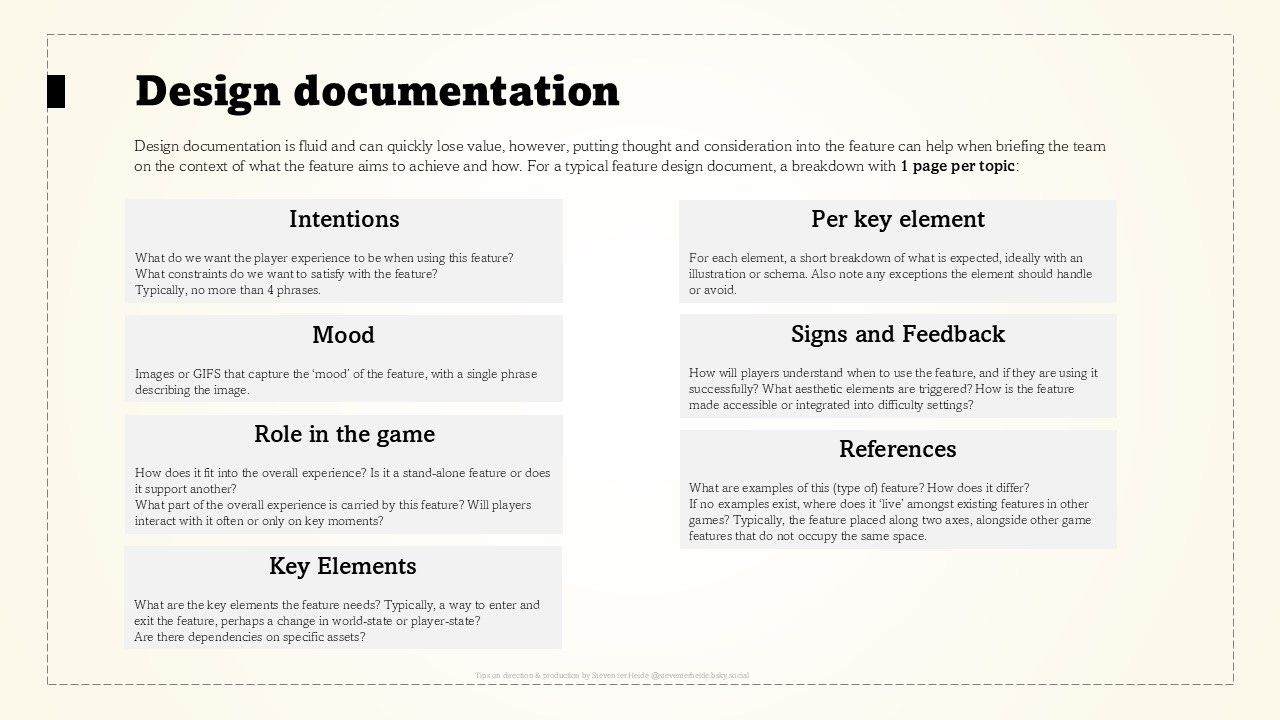

Design documentation is fluid and can quickly lose value, however, putting thought and consideration into the feature can help when briefing the team on the context of what the feature aims to achieve and how. For a typical feature design document, a breakdown with 1 page per topic:

Intentions

What do we want the player experience to be when using this feature?

What constraints do we want to satisfy with the feature?

Typically, no more than 4 phrases.

Mood

Images or GIFS that capture the ‘mood’ of the feature, with a single phrase describing the image.

Role in the game

How does it fit into the overall experience? Is it a stand-alone feature or does it support another?

What part of the overall experience is carried by this feature? Will players interact with it often or only on key moments?

Key Elements

What are the key elements the feature needs? Typically, a way to enter and exit the feature, perhaps a change in world-state or player-state?

Are there dependencies on specific assets?

Per key element

For each element, a short breakdown of what is expected, ideally with an illustration or schema. Also note any exceptions the element should handle or avoid.

Signs and Feedback

How will players understand when to use the feature, and if they are using it successfully?

What aesthetic elements are triggered?

How is the feature made accessible or integrated into difficulty settings?

References

What are examples of this (type of) feature? How does it differ?

If no examples exist, where does it ‘live’ amongst existing features in other games? Typically, the feature placed along two axes, alongside other game features that do not occupy the same space.

9. Aligning what you are making, how you are making it and with who can help increase your chances of success

Producers find ways to increase the chances of a project’s success.

Every game project has three key elements that require attention from production:

•Product; Can it be a critical, financial success?

•People; Does the team have everything to succeed?

•Process; It is clear how we are going to get over the finish line?

By aligning these elements as much as possible, we can boost the chances of success. This involves asking the right questions and adjusting the product, people, and process accordingly:

•Is the product well-suited to the team we have?

•Is the proposition clear and is there a shared enthusiasm for it?

•Does the development process fit the team and the product?

•Are the milestones aligned with the risks?

Depending on your situation and environment, some adjustments may be easier or harder to make.

10. People will tell you what THEY want the game to be, but that is not what you are looking for

To validate any design, we should look for feedback often and from as many different people as possible.

People however tend to provide solutions or tell you what they want the game to be.

While listening to their feedback, reflect on the underlying meaning of their comments and consider:

•🔎 Are they having the experience you wanted them to have?

•🎉 Are they enjoying the game in an unexpected way?

•🚧 Identify what might be hindering them from having (more) fun.

11. First impressions matter

Your game needs to make a strong first impression to attract its audience.

There are many ways people can be ‘watching’ your game, from streams to watching people play at events to sitting on the bus.

Use a clear visual hook, that makes people want to try the game for themselves or at least continue watching.

Consider the following:

•At a glance, the screen should capture the eye

•What is on the screen should be easy to understand (typically 3 main elements: the player, the challenge and the world it takes place in)

•The player's goal should be obvious.

•It should look satisfying to perform impressive ‘moves’

•Avoid ‘dead’ time spent in menus, reading long texts, lengthy respawns or loading, as these create moments to disengage.

12. On smaller teams, we should not forget about roles that are required to make a functioning team

Team leadership requires different attributes, often split into different people: Director, Lead and Manager.

The director is responsible for demanding quality, setting the expectations. The lead is responsible for delivering quality with the team. The manager is responsible for creating the conditions to allow quality to be created.

Ensure each of these roles is accounted for, even when it is all the same person. In typical productions, the management aspect is often a luxury, yet arguable one of the most important roles.

A manager focuses on three areas:

•🧑🏽🤝🧑🏽 People; balancing the needs of the project with people’s ambitions and capabilities as well as shaping a balanced team in terms of personalities, knowledge, skills and experience through hiring, firing and talent development.

•🧫 Process; creating and enforcing processes based on best practices that deliver the best results at the right time and cost, including internal and external dependencies

•🛠️ Tools; actively improving or creating tools that will improve efficiency and quality of life for the developers and their processes

13. Maslow's hierarchy of needs can be a guiding principle for game design too

To help guide and focus design we can think in hierarchical layers.

The American psychologist Abraham Maslow defined a hierarchy of needs. We can adapt this to games, allowing us to guide our design by ensuring the basic player needs are met before we move up.

We can define the player hierarchy of needs as follows, in order of priority:

1.Physiological: Can I control the game?

2.Safety: Can I overcome problems, avoid failing?

3.Belonging: Do I feel a connection with the characters, world, other players?

4.Esteem: Can I show progress towards set goals?

5.Self-actualization: Can I set my own goals?

In addition, by using this hierarchy, we can more easily understand where design problems originate, as we cannot achieve the next step without the previous.

13. Players can be thought of as actors in your game, how can you use this?

A unique quality of games is that they are interactive. We can make better experiences by taking care of the players, the individuals who interact with the game.

Players come into the game with expectations, a pre-existing mental model and a certain skillset.

A way to think about what we are asking them to do, is as if they were actors in a play. We want them to embody a specific role so that the game will offer the prepared, wonderful response.

Provide players with what they need:

•🎥 Set the stage; The introduction should make clear what will be expected of players in terms of gameplay, story and their role in it

•🧗 Provide the motivation; Reward the behavior we want players to exhibit

•⛑️ Support; Assist players in understanding and navigating the game, give them the tools to match their skillset.

14. Creating the right conditions to be creative and let creativity out is important

It is easy to get stuck in a maze of constraints and competing or conflicting voices, but often our inner-child can find the way forward.

By approaching ideas and creative challenges with a child’s perspective we reconnect with important child-like qualities:

•🤯 Honesty, openness and directness

•🌊 Authenticity, originality and purity

•🤸 Fun from simple things

•💖 Emotionally connected

So, when managing creativity or getting into a creative mode, find a way to let the inner-child speak.

•🤝Create a safe space where failure is welcome

•👐 Avoid feedback or filtering during the creative process (ok to put constraints upfront)

•👍 Encourage ‘Yes, and’ to add to and combine ideas (no room for ‘No, but’)

15. Curiosity is strong motivator and help for building engaging worlds

We can convince players to spend time in our world by skillfully combining aesthetic, narrative and gameplay to lead to playful discovery.

David Mamet, an American playwright and director once said:

“Forget narrative, backstory, characterization, exposition, all of that. Just make the audience want to know what happens next!”

Embracing this philosophy, we recognize it is curiosity that keeps players going. So, when designing we need to consider how we nourish and pay off this curiosity:

•🖼️ Aesthetically; How do the aesthetic elements change with time or place to enhance the journey of discovery?

•📖 Narratively; What narrative beats will players encounter, how does the journey resolve in a satisfying way?

•🕹️ Gameplay; What new experiences or challenges will players encounter? How will players master the game?

16. Presenting your game or idea is something you will have to do all the time

Convince and inspire people with strong presentation skills.

During development, we often present complex topics to a diverse group of internal and external audiences. They have very different backgrounds and information needs. Be empathetic but stay focused on your message.

📜 The form you choose for your presentation can set the tone without having to be explicitly mentioned. Talking about polish with polished slides helps support your message.

🎭 Choose the persona who is presenting, is it authentically you? Or do you choose an alter-ego who helps you in presenting or getting a specific message across?

⏳ Be explicit, remove ambiguity and keep it concise. Metaphors or comparisons may be shortcuts, but specify what you mean exactly. For example, of something is ‘like this movie’ explain what aspect of the movie you are referring to.

❓ Talk about the unknowns but be clear about what you are doing to turn the unknown into known, and by when.

17. Rough edges can cause frustration

You will want to remove any obstacles to having fun in the game.

Games are designed to offer challenges to players, set goals to achieve and present decisions to make. It is a careful balancing act to make sure we’re not breaking the second-to-second fun.

The games’ fun needs to be present in the second-to-second, and this is where we want to make sure we ‘sandpaper over any obstacles’, removing rough edges :

1.⚖️ Favor the players; Where possible, help players get more out of the second-to-second by tipping the scales in their favor. For example, with non-linear health or damage output.

2.🧈 Remove friction; Understand the players intent and see how we can remove unnecessary friction from achieving what they would like to do. For example, with supportive mechanics that help them succeed like power-ups, coyote-jump, aim assist, etc.

But do not forget about the barriers to entry that need to be removed through accessibility options for the game to be able to be enjoyed at all.

18. Be ruthless about what belongs in the game and what doesn't

To deliver a good quality game, remove everything that does not fit or belong, the sooner this is done, the better.

It is difficult to decide which features to keep, while satisfying the ‘business’ constraints of time, quality and scope.

In film-editing, scenes or lines that don’t advance the story meaningfully are often cut. We too should adopt an ‘editing’ mindset.

By ruthlessly removing features (content) we can:

•gain time: no polishing or bug-fixing unnecessary content

•increase quality overall: no low-value features, more time spent on the good stuff

•have a scope that fits the game: good features receive the spotlight

Consider:

•📌 Prioritize creating a memorable experience, rather than duration

•🪓 Can keep good features, but must remove bad features

•🎢 Ensure nothing overstays its welcome

19. Design around all of the senses, it will be surprising how many new feedback mechanisms you can use

Our senses, consciously and unconsciously combine to form as complete a sensation as possible.

Games underserve our senses, by not using them to their full extent, or by forgoing some by limitations in interfaces.

Through compensation and exaggeration, we can attempt to mimic or evoke emotions that otherwise require more sensory inputs. Consider these well-known ‘tricks’ and apply them to different conditions:

•👁️ Dynamically adapting color saturation

•👁️ Boosting certain colors or lighting for certain situations

•👁️ Modifying the aspect ratio dynamically

•👂 Switching between different sound reproduction (surround, mono, etc)

•👂 Introducing (short) moments of silence

•🧠 Celebrating player agency

•🖐️ Applying haptic feedback

20. Playtest, and playtest and playtest

Playtests are a valuable source of information and should be done as often as possible.

The value of a playtest is determined by the quality of the organization: is the game ‘ready’ for testing, are testers available, questionnaires prepared, game telemetry set up, etc.

Each game has unique parameters and requires a tailor-made test plan, but there are some common best-practices:

•📊 Set up in-game telemetry; Think about the data that would help you understand players intentions

•🎯 Decide the test objective; make sure the build is ready to be tested against this objective, discard other information not part of this objective.

•🧪 Test the test; at least once, go through the test yourself to see all elements working

•👨❤️👨 Do not side with testers; even if they like the game you want to be objective in the analysis

•💬 Follow up with testers based on data; You want the root-cause, not the symptoms.